“How much protein should I eat?”

Besides your unique biology, current condition and activities, the important decision for how much protein to consume depends on your age and the amino acid content of the protein choices. Older people need more, and too much methionine can be a significant problem.

Please note: There is strong evidence that both too little or too much protein can be deleterious in a variety of interconnected ways, and a person’s age and the protein source make a big difference. For longevity, the source of protein may have more of an impact even than caloric restriction. Recommended amounts stratified by age followed by a summary table for quick reference are at the bottom of this post, but please bear in mind that individual differences as reflected in multiple relevant lab values seen in the context of a complete clinical picture determine a personal recommendation.

Research published in EBioMedicine, part of the prestigious The Lancet portfolio of medical journals, offers helpful insight into how to choose the right amount of protein. This is an important consideration because, besides strength and locomotion, muscle is a major immunologic and metabolic ‘organ’ that contributes to immune system and metabolic regulation, especially blood glucose levels. While protein is crucial for maintaining or increasing muscle mass (and other protein structures in the body), too much can become a risk factor for chronic disease and mortality. At the same time, however, protein requirements go up with age and an insufficient amount results in sarcopenia, the loss of muscle mass, which is a biological calamity for aging that impacts multiple systems throughout the body due to the role of muscle tissue as an immunologic and metabolic organ.

The authors state:

“Lifespan and metabolic health are influenced by dietary nutrients. Recent studies show that a reduced protein intake or low-protein/high-carbohydrate diet plays a critical role in longevity/metabolic health. Additionally, specific amino acids (AAs), including methionine or branched-chain AAs (BCAAs), are associated with the regulation of lifespan/ageing and metabolism through multiple mechanisms. Therefore, methionine or BCAAs restriction may lead to the benefits on longevity/metabolic health. Moreover, epidemiological studies show that a high intake of animal protein, particularly red meat, which contains high levels of methionine and BCAAs, may be related to the promotion of age-related diseases. Therefore, a low animal protein diet, particularly a diet low in red meat, may provide health benefits. However, malnutrition, including sarcopenia/frailty due to inadequate protein intake, is harmful to longevity/metabolic health.”

The essential AAs (EAAs), such as BCAAs (branched chain amino acids) and methionine are especially involved in regulating aging process and metabolic health through multiple physiological and molecular mechanisms.

More important than caloric restriction

The authors note:

“Dietary interventions, including calorie restriction (CR), dietary restriction (DR), and protein restriction (PR), have been investigated for their effects on longevity or the prevention of age-related diseases through their effects on metabolic health. CR without malnutrition has been shown to extend the lifespan and improve metabolic health in organisms [1]. However, recent evidence indicates that the quantity, source and amino acid (AA) composition of proteins are more strongly associated with longevity and metabolic health than CR [2]. The macronutrient balance of diets, including low protein/high carbohydrate (LPHC) diets, has been shown to have the greatest significant impact on longevity and metabolic health [[3], [4], [5]].”

mTORC1, Gnmt and SAM, FGF21, GH, IGF-1, H2S

mTORC1

To understand protein metabolism it’s especially important to recognize the role of the Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex1 (mTORC1) and its importance to autophagy, the critical process by which worn out, damaged and senescent cells are removed by the immune system. As the authors note:

“mTORC1, a subunit of mTOR, is a serine/threonine kinase that acts as a central regulator of cell growth and metabolism in response to nutrients and growth factors [14]. mTORC1 is activated by various factors, including AAs [14,15] and is the primary modulator of protein, lipid, and nucleotide synthesis; autophagy; and insulin signalling [14]. The pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin has been shown to extend the lifespan and exert beneficial effects on a set of ageing-related traits in mice, indicating that mTORC1 may be related to lifespan regulation [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20]]. Nutritional interventions, such as a LPD [low protein diet], also suppress mTORC1 because AAs promote mTORC1 activation [15].”

In particular, reduced levels of leucine and arginine lead to the suppression of mTORC1 activation. The suppression of mTORC1 is associated with the induction of autophagy and improvement of insulin resistance, resulting in longevity and metabolic health.

Glycine N-methyltransferase (Gnmt) and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) metabolism

SAM is converted to S-adenosylhomocysteine by Gnmt…Recent reports have shown that SAM, rather than methionine, may be the main contributor to methionine restriction (MetR)-induced lifespan extension.

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21)

FGF21 is an endocrine signaling factor in PR and is associated with lifespan extension, metabolic control and organ protection. Levels increase on a LPD (low protein diet) regardless of the overall caloric intake in both rodents and humans [31]. The increased circulating levels of FGF21 play a role in the regulation of glucose/lipid homeostasis, mitochondrial activity, ketogenesis and energy expenditure (EE), which could be expected to be beneficial for age-related health.

Growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-1 (GH/IGF-1)

“Reduced GH/IGF-1 signalling is linked to survival duration and decreased incidence of cancer and T2DM in humans [44,45]. Reducing IGF-1 signalling suppresses the ageing process…PR (protein restriction) or restriction of particular AAs such as methionine, may explain part of the effects of CR on longevity and disease risk because PR and AA restriction can sufficiently reduce IGF-1 levels and cancer incidence and extend the lifespan in model organisms independently of calorie intake [46].”

Hydrogen sulphate (H2S)

The restriction of dietary sulfur-containing AAs (SAAs), including methionine, leads to stress resistance and longevity by increasing H2S production.

“H2S can readily diffuse through tissues and has pleiotropic and beneficial effects at the cellular, tissue and organismal levels with the potential to contribute to stress resistance by exerting positive effects, including anti-oxidative/anti-inflammatory effects [53].”

Oxidative stress and inflammation

“Mitochondria are recognized as major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the oxidative damage associated with mitochondria is involved in mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular ageing….A 40%PR (protein restriction) diet for 6–7 weeks without CR (calorie restriction) also decreases mitochondrial ROS (MtROS) production…Additionally, both 80% and 40% MetR (methionne restriction) without CR for 6–7 weeks decreased MtROS generation…BCAAs also cause oxidative stress and inflammation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells [61] and endothelial cells [62] via the activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mTORC1.”

The protein source may be more important than the amount

The authors state:

“The protein source, including animal or plant protein, may be more important for mortality risk than the level of protein intake.”

Red meat, which high in branched chain amino acids and methionine, and especially processed red meat, did not do well in a prospective US cohort study involving 131,342 participants over 32 follow-up years [7].

“Among animal proteins, the consumption of red meat and processed meat is associated with the risk of developing chronic diseases, including CVD, CKD [chronic kidney disease], cancer and diabetes [8,9]. A meta-analysis indicated that a high consumption of red meat tends to increase the risk of CVD mortality and cancer and that a high consumption of processed meat significantly increases the risk of cancer and CVD mortality and diabetes [8]. Red meat is an important dietary source of EAAs and micronutrients, including vitamins, iron and zinc, that perform many beneficial functions. However, a high intake of red meat and processed meat results in an increased intake of saturated fat, cholesterol, iron, salt, and phosphate; oxidative stress/inflammation; elevation of by-products of protein or AA digestion by the gut microbiota, such as trimethylamine n-oxide or indoxyl sulfate; acid load; and protein/AA load, which are possibly associated with increased risks of CVD mortality and CKD.”

Branched Chain Amino Acids

BCAAs (valine, leucine, and isoleucine) have important benefits for mitochondrial function but excess levels may be harmful for longevity and metabolic health, particularly in the context of obesity, T2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (which are closely associated with each other).

“…the supplementation of BCAAs abolishes the effect of PR [protein restriction] on glucose metabolism and induces inflammation in visceral adipose tissue in mice [10]. In epidemiological studies, there is a positive relationship between increased circulating BCAA levels and insulin resistance in obese and diabetic patients [[75], [76], [77]] and CVD patients [[78], [79], [80], [81]]. Additionally, the increased circulating BCAAs are possibly due to abnormal BCAA metabolism associated with obesity resulting in an accumulation of toxic BCAA metabolites that, in turn, trigger mitochondrial dysfunction, which is associated with insulin resistance and T2DM [82].”

HOWEVER:

It’s a different story when we get older (recommended amounts of protein per day according to age groups are at the bottom of this post).

“…several clinical studies have also shown that BCAA supplements reduce sarcopenia in elderly people and exert beneficial effects on body fat and glucose metabolism, possibly by increasing mitochondrial biogenesis and muscle function [84].”

“Thus, the high intake of BCAAs due to excessive food intake in obese people is harmful in terms of insulin resistance and T2DM. However, a low level of BCAA intake in elderly people is also harmful in terms of sarcopenia. Therefore, the appropriate intake of BCAAs for individuals is necessary to maintain longevity and metabolic health.”

Methionine

“Met is directly involved in promoting the ageing process through multiple mechanisms.”

Dietary restriction of the amino acid methionine (methionine restriction = MetR) has shown a number of benefits across a range of organisms.

“MetR increases metabolic flexibility and overall insulin sensitivity and improves lipid metabolism while decreasing systemic inflammation [42,88,90]. …MetR produced a significant increase in fat oxidation and a reduction in intrahepatic lipid content [91]. Additionally, Virtanen et al. reported that the relative risk of an acute coronary event in individuals with a high methionine intake (>2.2 g methionine/day) was higher than that of individuals with a low methionine intake (<1.7 g methionine/day) in a prospective cohort study (1981 men, aged 42–60 years at baseline, average 14.0 years of follow-up) [92].

Additionally, plasma SAM [S-adenyl-methionine] concentrations were associated with higher fasting insulin levels, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance and tumour necrosis factor-α in a cross-sectional study involving 118 subjects with metabolic syndrome [93]. Another report demonstrated that plasma SAM, but not methionine, is independently associated with fat mass and truncal adiposity in a cross-sectional study involving 610 elderly people [94], while overfeeding increases serum SAM in proportion to the fat mass gained [95]. Thus, increased SAM related to overfeeding or metabolic dysfunction may be associated with whole body metabolic impairment.”

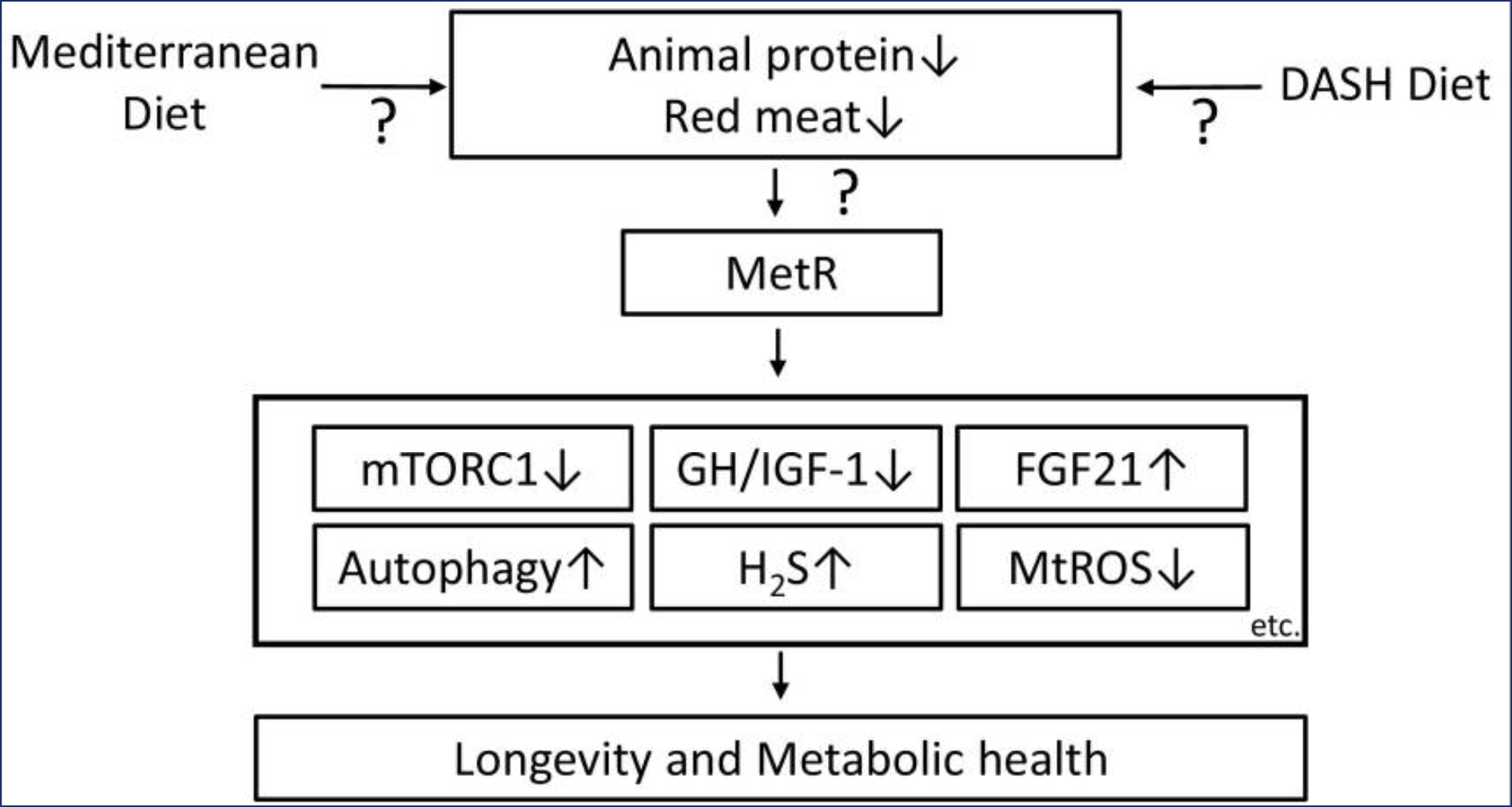

MetR [methionine restriction] may be a candidate dietary intervention for longevity and metabolic health through its effects that are exerted via multiple mechanisms. A Mediterranean diet or the DASH diet may be useful for reducing the consumption of animal protein, particularly red meat, to achieve MetR.

A balanced approach

The authors offer a balanced perspective in their conclusion:

“Among dietary interventions, MetR may be a candidate intervention for longevity and metabolic health (Fig. 4). Food sources of animal protein, such as beef, lamb, fish, pork and eggs, contain higher levels of methionine than plant food sources, including nuts, seeds, legumes, cereals, vegetables and fruits [96]. Therefore, an individual may need to eat less animal-based food to achieve MetR. For example, the Mediterranean diet [97] or the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet [98] may be useful for decreasing the consumption of animal protein, particularly red meat (Fig. 4). However, red meat is an important dietary source of micronutrients, including vitamins, iron and zinc; therefore, an appropriate intake is necessary to avoid malnutrition.”

And:

“…reduced protein intake does not decrease the potentially negative effects of certain types of carbohydrates and fats.”

“…methionine or BCAAs restriction may lead to the benefits on longevity/metabolic health. Moreover, epidemiological studies show that a high intake of animal protein, particularly red meat, which contains high levels of methionine and BCAAs, may be related to the promotion of age-related diseases. Therefore, a low animal protein diet, particularly a diet low in red meat, may provide health benefits. However, malnutrition, including sarcopenia/frailty due to inadequate protein intake, is harmful to longevity/metabolic health.”

Important

As always, there is no ‘one size fits all’. Individuals vary greatly in their metabolism, digestive capacity, GI microbiome, mitochondrial function, activity levels, immune regulation of inflammation, oxidative burden, glucose and insulin regulation, and a host of factors that can be measured with the appropriate tests to translate this information from a general perspective to an individual recommendation.

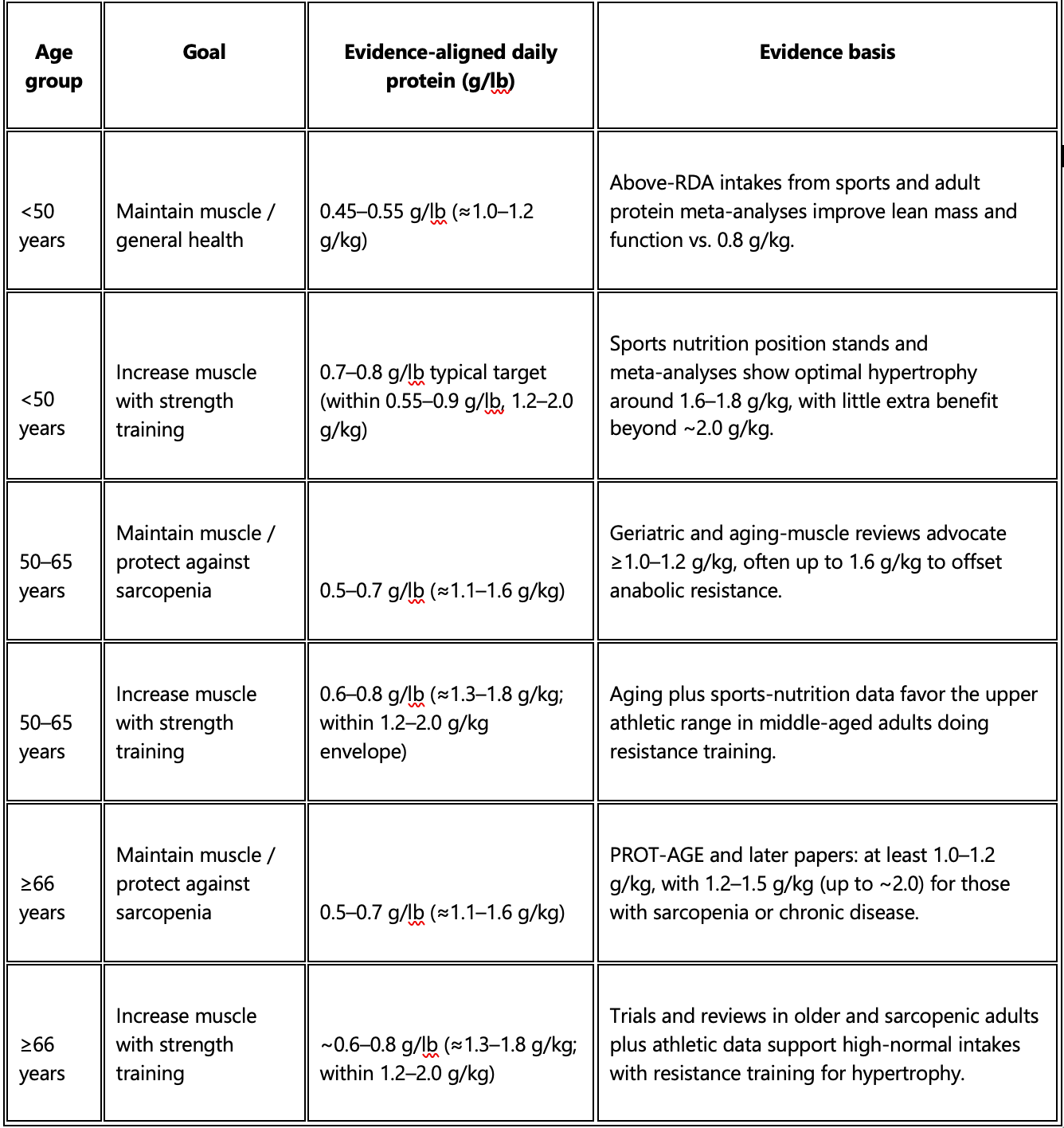

Recommended amounts by age

For healthy adults, peer‑reviewed position papers and meta‑analyses generally converge on about 0.7–0.8 g protein per pound per day to build muscle with resistance training, and somewhat less (≈0.45–0.6 g/lb) to maintain muscle and reduce sarcopenia risk, with higher intakes emphasized in older age groups. Scroll down to see the table below which converts leading evidence‑based recommendations (mostly in g/kg) into grams per pound of body weight.

(Conversion used: 1 kg ≈ 2.2 lb, so g/kg ÷ 2.2 ≈ g/lb.)

Younger than 50 years

Evidence here mostly comes from general adult and sports‑nutrition literature, which does not show an increased baseline requirement solely due to age below ~50.canr.msu+3

To maintain muscle / reduce future sarcopenia risk

General adult minimum (RDA equivalent): ~0.36 g/lb (0.8 g/kg) – this prevents deficiency but is likely suboptimal for long‑term muscle preservation.nasm+1

Evidence‑based “better than RDA” range from meta‑analyses and sports nutrition data: 0.45–0.55 g/lb/day (≈1.0–1.2 g/kg/day).pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+1

To increase muscle with strength training

Sports nutrition and meta‑analytic data: 0.55–0.9 g/lb/day (≈1.2–2.0 g/kg/day) optimizes gains in lean mass and strength when combined with resistance training.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+3

Many trials and position stands cluster most hypertrophy benefits around ~0.7–0.8 g/lb (~1.6–1.8 g/kg), with little additional benefit beyond ~0.82–0.91 g/lb for most lifters.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+1

Age 50–65 years

From about midlife onward, sarcopenia risk rises and several expert groups and reviews advocate higher daily protein than the 0.8 g/kg RDA, even in healthy adults.mayoclinichealthsystem+5

To maintain muscle / protect against sarcopenia

Reviews and geriatric nutrition position papers: 1.0–1.2 g/kg/day is recommended as a baseline for older adults, which translates to ~0.45–0.55 g/lb/day.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+3

Some analyses and expert reviews propose 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day to better counter anabolic resistance in this age band, i.e., ~0.55–0.73 g/lb/day.frontiersin+2

To increase muscle with strength training

Combining aging and resistance‑training data, many authors recommend staying toward the high end of the “athletic” range: 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day (~0.55–0.73 g/lb/day) as a practical target, with room up to about 2.0 g/kg/day (~0.9 g/lb/day) if tolerated and clinically appropriate.academic.oup+4

This aligns with evidence that older adults often need higher per‑meal and total daily protein to stimulate maximal muscle protein synthesis compared with younger adults.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+3

Age 66 years and older

In this group, sarcopenia and frailty become central concerns, and the strongest evidence base (PROT‑AGE and subsequent papers) supports substantially higher protein than the 0.8 g/kg RDA.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+5

To maintain muscle / protect against sarcopenia

PROT‑AGE Study Group and later reviews: 1.0–1.2 g/kg/day for generally healthy adults ≥65 years to maintain or regain lean mass and function: ~0.45–0.55 g/lb/day.researchexperts.utmb+3

For those at risk of or with sarcopenia, or with chronic disease, recommended intakes commonly increase to 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day (sometimes up to ~2.0 g/kg), corresponding to ~0.55–0.68 g/lb/day (upper illness‑related targets ≈0.9 g/lb/day).espen+4

To increase muscle with strength training

Reviews on protein and aging plus sports‑nutrition data support ~1.2–1.6 g/kg/day (~0.55–0.73 g/lb/day) as a realistic, evidence‑supported range for hypertrophy and strength gains in older adults when combined with resistance training.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+5

For sarcopenic or frail older adults engaged in supervised resistance programs, some clinical trials show benefit up to about 1.5 g/kg/day (~0.68 g/lb/day), with suggestions that 1.5–2.0 g/kg/day (~0.68–0.9 g/lb/day) may be appropriate in selected, medically monitored cases.espen+4

These are rounded, evidence‑aligned ranges, not rigid prescriptions; clinical conditions (kidney disease, liver disease, etc.) can alter safe upper limits. Because kidney and other comorbidities are common in older adults, these ranges should be individualized with a clinician or dietitian, especially when approaching or exceeding ~0.8–0.9 g/lb (~1.8–2.0 g/kg) per day.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+3